|

Michael Speechley and Octavia Foundation staff move the shrine ready for it to go on display at the Tate Britain.

0 Comments

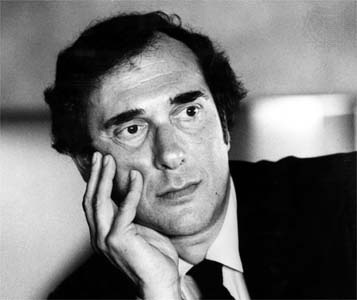

By Gopesh Pathak It seems only fitting that such an important dramatist should have led such a dramatic life. Harold Pinter’s contribution to theatrical drama spanned many decades and blossomed alongside his ventures as an actor, screenwriter and director which saw him become one of the most iconic figures of art in this country for many-a-generation. Born to Jewish parents of Eastern European origin in Hackney, Pinter renounced his Judaism after his bar mitzvah at the age of thirteen and died a vociferous anti-Israel campaigner. He was an equally vociferous campaigner for human rights – so much so that, upon receiving his Nobel Prize, the majority of his 45 minute acceptance speech was an incredibly vituperative tirade against US foreign policy. Pinter was one of the most influential voices in support of the “Stop the War” campaign in 2003. Thanks to evacuation during the war, Pinter was separated from his parents for much of his early youth. He was, however, with them in London during the Blitz; something that would go on to have a profound impact on his future political beliefs. As near in the future as 1948, in fact, which saw Pinter refuse to do his National Service. Though he is often referred to as a pacifist for his anti-war activism as well as this refusal, it is an inaccurate adjective to attribute to him as, in the tribunal relating to his refusal, Pinter claimed that he would have fought in the Second World War had he been of age to do so as that was a war against injustice. The Cold War, however, was deemed by Pinter to be a war of injustice. In the end, he was issued with a fine which his parents paid for him. Pinter began his career as an actor. Having gained a scholarship at RADA, a famous Drama school which was at the time, dominated by students of wealthy beginnings, Pinter could not stand the environment and chose to truant and read Kafka’s work in Hackney library instead. He did go on to become an actor both on stage and radio for productions of others’ plays as well as his own. But it was undoubtedly writing which gave him the most pleasure and it is his achievements as a writer that have ultimately secured his place in history books across the globe. As a writer, Harold Pinter was a masterful innovator. His manipulation of absurd theatre, colloquial dialogue in everyday settings and his use of silences have led to the term “Pinteresque” adorning the collective consciousness of the drama world (as well as the Oxford Dictionary). As for the man himself; well, he would beg to differ. He has gone on record to say that he does not have the faintest idea as to what Pinteresque could possibly be referring to, but it would be fair to say that there are certain qualities one can only find in his plays. That said, being an innovator has its own cost, as the critical reception of Pinter’s first major play The Birthday Party (1958) all too clearly revealed. Almost unanimously ridiculed (it was even branded “imbecilic” by one critic), Pinter’s deployment of what would go on to be his trademark trivial dialogue and unresolved ending was not understood by the critics who were more familiar with less ambiguity which was the accepted form at the time. Pinter’s disdain for norms in his plays was evident in his private life too and his marriage to his first wife, Vivien Merchant, without the blessing (or knowledge) of his parents (during the Jewish festival Yom Kippur!) was something which quite possibly saved his career. The poor reception of The Birthday Party saw Pinter on the verge of quitting playwriting altogether. It was Vivien who told him to continue and it was Patrick Magee, one of Pinter’s friends from his days as an actor, who managed to get a BBC radio producer to give Pinter an opportunity on the basis that if he didn’t get a job, he’d give up. From there on in, Pinter’s career went from strength to strength and he started getting appreciated for his unique approach to forming a plot. The Caretaker (1960), based on his personal experience, saw Pinter’s recognition reach new heights and moved him from being a dramatical Tahiti to a dramatical China. But, just as China is vulnerable to earthquakes, so to was Pinter and The Caretaker saw his marriage to Vivien collapse. His increased fame was at odds with Vivien Merchant’s own career as an actress, and having been the more successful partner up until that point, Vivien Merchant perhaps felt a loss of power. She also had great anger towards The Caretaker due to its plot which she felt displayed ingratitude towards people they had encountered and so, despite her becoming the epitome of women in Pinter’s plays for the rest of the ‘60s, the distance between them grew and by 1975, they had a very public split. Having had an affair with journalist Joan Bakewell, Pinter also engaged in an affair with historian and wife of a Tory MP, Lady Antonia Fraser who he later married in 1980 and stayed with until his death. It would be a great disservice to Pinter to present his plays in a summarised fashion though, it must be said, that his public perception was one of a grumpy man who was not the slightest bit interested in small talk – the mark of which is seen with the ambiguous and trivial colloquial dialogue in his plays as well as with the many accounts of his hatred of the question “How are you?” Aside from his career, Pinter was an avid cricket fan and his enthusiasm for the game saw him play for and then manage his team, the Gaieties. Pinter was diagnosed with cancer of the oesophagus in 2002. He continued his work however, directing a production of No Man’s Land and overseeing two screenplays as well as becoming increasingly active in political writing – all of this whilst undergoing treatment. In 2005, Pinter announced he would no longer write any plays. Instead of directing plays, Pinter wanted to direct his energy towards political activism. Unfortunately, this coincided with a development of septicaemia and a rare skin disease which limited his mobility. Though he continued admirably to produce material in the form of poetry and screenplay adaptations – most notably a poem entitled Cancer Cells which was widely-acclaimed for its wonderful language and dark humour – on Christmas Eve in 2008, Harold Pinter succumbed to his illness (liver cancer) and news of his death touched people all over the world. A testament to his political prowess came in the shape of a tribute from the late left-wing powerhouse Tony Benn. As for his impact on drama, that is more than words can express. Perhaps the fact he had arranged for Michael Gambon to read an extract from his play is the most glowing example of his attention to detail and desire for perfection and of how, in his most impressive shadow, even the greatest of giants seek shade. |

AuthorContent from the Waking the Dead digital media team and volunteers. Archives

April 2017

Categories |

- Home

- The Project

-

Key Figures

- Andrew Ducrow

- Anthony Perry

- Anthony Trollope

- Baron Baker

- Charles Babbage

- Count Suckle

- Duke Vin

- James Barry, Dr

- Feargus O'Connor

- Frank Critchlow

- Harold Pinter

- Howard Staunton

- Isambard Kingdom Brunel & Marc Isambard Brunel

- George Bridgetower

- Jind Kaur

- Joe Strummer

- Kate Meyrick

- Kelso Cochrane

- Michael Abbensetts

- Pearl Connor

- Russ Henderson

- Thomas Wakley

- Wilkie Collins

- William Makepeace Thackeray

- The Reformers Memorial

- The Dissenters' Chapel

- The Exhibition

- Gallery

- Waking the Dead Blog

- Contact

- Links

RSS Feed

RSS Feed