|

It was recently reported that Isambard Kingdom Brunel had specially designed the Box tunnel so that the sun shines through the tunnel for his birthday (9th April). Talk about showing off!?

Brunel features in the the Waking the Dead app that can be downloaded from the App Store and Google Play. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2017/apr/10/isambard-kingdom-brunel-birthday-box-tunnel-bath-sun http://www.bathchronicle.co.uk/did-brunel-design-the-box-tunnel-so-that-the-light-would-shine-through-at-sunrise-on-his-birthday/story-30258983-detail/story.html

0 Comments

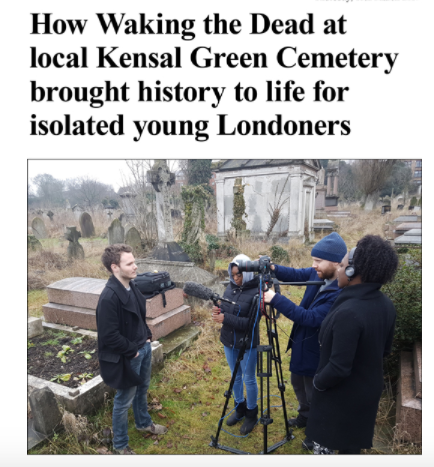

Great article from London Youth on Waking the Dead... http://londonyouth.org/news-and-events/news/waking-the-dead-with-octavia-foundation/ The Waking the Dead project has changed my attitude towards cemeteries. Before engaging in this project, cemeteries were dead places to me; sacred, yet guarded by norms. Society demands constant respect for the dead, as if they can be disturbed by the noises, voices and actions of the living. However, throughout the project, the cemetery began to morph. It stopped being a place of self-imposed quiet and more an interactive archive, through which a better understanding of the world can emerge. With this change in apprehension came a change in behaviour. The morose reflections stopped and respect for the dead no longer meant confining them to their space and leaving it in peace. Looking at graves, so many graves, and reading the inscriptions or lack thereof, I began asking ‘who are they?’ ‘What did they do?’ ‘Does anybody still remember them?’

As a space, the thing that strikes me most about Kensal Green Cemetery is how many of the stones have been eroded. Many memorials to the dead have become illegible. Many burial spots therefore become a space that demand respect, but to an unknown figure. This is obviously not a new thing. A name doesn’t exactly mean anything unless you associate it with someone, it is as vacant as any other descriptor that doesn’t latch. Tombs to the Unknown Soldier are common in places ravaged by war, but Kensal Green Cemetery has many people who are unknown. Therefore, a project that seeks to ‘wake the dead’ - even if it had a wider scope and longer time frame - would only ever be able to scratch the surface. A project that really engaged in the social archaeology of a space like this in London would require teams of researchers. Who do we place the camera’s lens on? Who should be geo-located and written upon? This list constantly changed. The people we focussed on were not in any way exhaustive, nor were they perhaps the best reflection of the space. The lack of women remembered in history is problematic and remains a problem within this project. We wanted more, we sought to include many more, however, many were famous for salacious behaviours or scandal. This did not chime well. The women who were paid tribute to were towering figures: Pearl Connor-Mgotsi and Kate Meyrick in particular. We also remembered a lot of the recent history of the political and cultural giants from the African-Caribbean communities of the local area, people like Hubert ‘Baron’ Baker – who is paid respect to in the app for his political commitments or Michael Abbensetts, who is remembered for his contributions to the theatre. One person who warrants much greater attention who we were unable to do the work on is Aunt Suzy, a matriarch of the Caribbean community, who formed a credit union and networking site on Blenheim Crescent just after the first communities from the Caribbean began to settle in North Kensington. As Charlie Phillips told us, the network assisted Caribbeans as they arrived to settle across the country, providing loans when banks refused to. The list of notable figures we didn’t cover could fill a book. What troubles me, however, is the number of people whose lives had impacts on individuals, the area and wider society but who were not celebrated in print or media. A project of this nature cannot do justice to those gone, it does however reveal a process of how to do it. Lives are very rarely chronicled. Those who are remembered through the ages are not remembered for who they are, but for who remembers them and how. Those with the powers of communication determine the narrative and who should be remembered. Digital media provides an ability to capture the words, thoughts and reflections of people who do not write their memoirs and testimonies, for whatever reason. Filmed interviews, oral history recordings or photography can gather histories that the written form excludes. As archivists begin to digitise the information of the past, there’s a very exciting future for telling the stories that history, as it stands, misses. There are much more of the dead to wake. Summoning the strength of movements, people and ideas from the past can help us contend with the issues of the present and future. Daniel Renwick Michael Abbensetts sadly died in November 2016. The Octavia Foundation's young people met the esteemed writer in 2011 and interviewed him for the Margins to Mainstream project. He spoke passionately about breaking into the arts as a black writer, the challenges he faced and his motivations for becoming a playwright. He was a humorous and wonderfully warm man, who welcomed the team into his house and shared his personal story with us. We are very sad to hear of his passing and have made this film and paid tribute to him in the app to remember him and pay our respects. Rest in peace Michael. The work we have done with St Thomas C.E Primary School has ranged from spoken word training, art production, curation, film-making and more! Here are just a few snapshots of the work we've done... For the second film in the Waking the Dead project, we gathered young voices who reinterpreted some of the creative work of the artists buried or cremated at Kensal Green Cemetery. Here's some images from the filming! Hubert 'Baron' BakerWritten by Jamillah Harris

Hubert ‘Baron’ Baker was born in Jamaica in 1925. He arrived in Britain in 1944 when he joined the RAF as a policeman and continued to live in London for the remainder of his life. Baron Baker was described as an outspoken and charismatic man and strove throughout his life to combat the racism and inequality faced by black people living in Britain. He played a significant role in the famous 1958 race riots in North Kensington. At the age of 19, Baron Baker left Jamaica to join the RAF, feeling a strong affiliation with Britain, ‘The Motherland’, and eager to join in the fight for freedom against Hitler. Upon his arrival, he noticed that many Britons had never seen black people but claimed that his first experience of racism was in a pub in Gloucester when the American G.I.s serving with them believed that the black servicemen should not be allowed to join them in the pub. Baker, considering himself to be British and entitled to the same respect as white soldiers, refused to accept the American’s racist behaviour. He and his fellow British comrades fought to ensure this behaviour would not continue. After the Second World War, the British government revealed plans to forcibly send back Caribbeans that had served in the war. Angered by these plans and insisting that the contributions of black men and women in the war be acknowledged, Baron Baker resisted, threatening to take the matter to court. In order to avoid confrontation, the air force authorities agreed to allow the Caribbean servicemen and women to remain in Britain. When the Empire Windrush arrived in London from the Caribbean, Baron Baker was there to welcome the 492 West Indian migrants hoping to begin new lives in Britain. Baker persuaded Labour MPs to open an air raid shelter in Clapham South as temporary accommodation for the new arrivals. Because of this, many of the migrants were able to find employment and housing in nearby Brixton. Due to his role in assisting so many Caribbeans to settle in the area, Baker was regarded as ‘The man who discovered Brixton.' Despite his proud British sentiment and respectable effort during the war, Baker struggled to find employment and housing due to racist landlords and employment restrictions. He finally settled in Notting Hill Gate, where he continued to resist racism from the local residents. The growing presence of Caribbean migrants in the local area and the prevalence of racist public figures such as fascist politician Oswald Mosley, who campaigned to repatriate Caribbeans living in Britain, fuelled violent attacks on black people living in North Kensington. People were being attacked by ‘Teddy Boys’ and other white gangs in the streets and in their homes. Baron Baker and his friends recognised the need for resistance and worked collectively to protect members of the black community from racist attacks. Despite the authorities advising black people to stay indoors, Baker and other members of the community decided to fight back, refusing to tolerate the violent racist behaviour they were subjected to. Operating from their ‘headquarters’ Totobag’s Cafe, a black community centre at 9 Blenheim Crescent, Baron Baker and his friends operated a ‘neighbourhood watch’ style service, offering to assist any members of the community in arriving home safely and protected houses from attacks from white gang members. The struggle escalated when Majbritt Morrison, a white Swedish woman was arguing in public with her black Jamaican husband Raymond. Seeing this, white racists attacked Raymond in an attempt to ‘save’ Majbritt despite the fact that she did not want to be saved. The fight intensified when black onlookers joined to defend Raymond. Hearing about this incident angered many racists that wanted to get black people out of the local area. Soon after, white rioters planned an attack on number 9 Blenheim Crescent, and number 6 where the West Indian women would gather. Using his military experience, Baron Baker and his friends prepared to fight back. A mob of hundreds of angry, white rioters could be seen making their way to Blenheim Crescent; threatening to lynch and burn the black people living in the area. Those at number 9 fought back using Molotov cocktails - handmade firebombs - and successfully chased the rioters away. Baker was arrested after these events but his comrades continued the battle - which was later coined as the Battle of Blenheim Crescent. As well as physically combating the racist treatment of black people living in Britain, Baron Baker founded an organisation called the United Africa-Asia league, participated in anti-fascist groups, initiated campaigns for better housing for West Indian people, and spoke at Speakers Corner, Hyde Park about issues experienced by black people. Baker lived the remainder of his life in Notting Hill; he died in 1996. His funeral was held in Kensal Green Cemetery; where he was remembered as a respected and important member of the community. By Jamillah Harris

Kelso Cochrane, born in 1927, was an Antiguan Carpenter living in West London. In 1959, he was attacked and murdered by a gang of white men. His murder highlighted the hostility and racism that was rife at the time and marked the onset of anti-fascist movement and resistance in the area. On 17th May 1959, Kelso Cochrane was walking home from hospital on Southam Road, North Kensington, after sustaining a work injury when he was attacked and fatally stabbed by a group of 4 – 6 men. That night, there were a number of house parties on the same road and 3 groups of witnesses were present; a local resident claimed to have heard the group of attackers shouting racial abuse at Cochrane at the time of the incident. Cochrane, who was still conscious after the stabbing, informed those assisting him that the men also attempted to steal his belongings. Sadly, he died on the way to the hospital. Kelso’s murder is considered to be reflective of a time of building hostility and violence towards black people that had recently arrived in London and other parts of Britain. Having arrived in London on the Empire Windrush in 1948, many of the West Indian migrants settled in the slums of Notting Hill. In the years leading up towards Kelso’s murder, some white people living in the area would express their discontent at the West Indian presence. British fascist politician Oswald Mosley gained support of some racist locals with his plan to repatriate West Indians living in Britain, motivating people to act against the “evils of the coloured invasion”. Black people suffered violent attacks from ‘Teddy Boys’ in the streets and in their homes. In the summer of 1958, race riots further terrorised black residents of the North Kensington area and a violent conflict arose at Toto Bags, 9 Blenheim Crescent, a popular West Indian cafe and community centre. Following these events, 9 white rioters were prosecuted and given 4 year prison sentences. Families, friends and other members of the public were outraged by this decision, believing that the rioters did not deserve such punishment. The campaigns for ‘justice’ for the white rioters, as well as the continuing violence shown towards black people on a daily basis demonstrates the climate of hostility that allowed for Cochrane’s murder to take place. Those responsible for murdering Kelso Cochrane were never brought to justice and the police investigation of the murder came under much scrutiny. Friends, family, and members of the local community were outraged by their failure to convict those involved, despite the fact that the murderer was widely acknowledged to be a man called Pat Digby. The murder was reported in the press as a racial attack; however, the police handled the murder as an attempted robbery, denying the significance of race. There were many flaws in the procedures undertaken by the police attempting to solve the crime. Following the attack, Forbes Leith - the police officer in charge of the investigation – arrested Pat Digby and his friends. Digby and one of his friends were placed in adjoining cells, allowing for them to corroborate upon their stories. They were released after 12 hours. Claiming to have performed a thorough search for the weapon used to kill Cochrane, the police searched the canal and the drains in the surrounding area but never performed a rudimentary search of Digby’s house. Claims have been made that Digby hid the knife used to kill Cochrane under the floorboards of his house, however, the police never agreed to a search, meaning that the weapon could still be there. Considering that the murder took place at a time of capital punishment, it was considered by many that the police were unwilling to kill a white man for murdering a black man. Whether this is the result of racism within the police force, or of their reluctance to incite further racial tension, it is evident that not enough was done to bring Cochrane’s murderers to justice. In response to the police’s negligence of the case, many members of the local community acted in an attempt to gain justice for Cochrane. 1,200 people attended his funeral held at Kensal Green Cemetery; it was noticed that the demographic of those that were present was mixed, showing the magnitude of support and solidarity from the local community. Cochrane’s murder compelled Claudia Jones, editor of The West Indian Gazette, to engage others in the fight for justice, raising a movement against the mistreatment of non-white people in Britain. Campaigners marched to Downing Street in silent protest in an attempt to raise awareness of and gain justice for his murder. In 1962 Notting Hill Carnival was initiated in commemoration of the murder, and in 1965, new legislation was passed in an attempt to put a stop to racial violence and discrimination. However, Cochrane’s murderer had still not been brought to justice. In 2003, Kelso’s brother Stanley arrived in London from Antigua with the intention of reopening his brother’ murder case. However, Stanley was not met with the cooperation he expected from the police as he was informed there was no forensic evidence and that Kelso’s clothes had been incinerated in 1969. On hearing about this case, journalist Mark Olden offered to assist Stanley and made a freedom of information request to the Metropolitan Police. This request was denied on the grounds that the case may be reopened by the police despite their lack of intention to do so. Despite the lack of cooperation from police, Mark Olden was able to gain a greater understanding of the events that took place surrounding Cochrane’s murder by interviewing members of the local community. Following his investigation, Olden wrote his book ‘A Murder in Notting Hill’, naming Cochrane’s murder and rightfully suggesting that the murder was racially motivated. In 2009, 50 years after Kelso’s killing, in 2009, a Nubian Jak blue plaque was put up to mark the place of the murder. The plaque was commissioned by the 1958 Remembered:50YearsOn project led by local resident Isis Amlak and Cllr Pat Mason (Golborne Ward). Local artist, Alfonso Santana, created the mosaic portrait of Cochrane on his grave. The Kelso Cochrane 2009 initiative was led by the 1958 Remembered Project Manager Isis Amlak. Cochrane's death is marked annually on Southam Street. By Jamillah Harris

Frank Crichlow, affectionately known by many as the “Godfather of Grove”, was a legend of Ladbroke Grove’s Caribbean community. His funeral was considered one of the biggest known community events, with local roads being “shut down” due to the number of people who came to pay their respects. He was cremated in the West London Crematorium of Kensal Green Cemetery. Crichlow is well remembered for his role as a crucial civil rights campaigner and for setting up the Mangrove – a community hub and famous restaurant, previously located at 8 All Saints Road. Crichlow was born in Port of Spain, Trinidad in 1932 and moved to London in 1953. Like many Caribbean migrants, Crichlow worked on the railways when he first came to the UK. In 1955, he became the bandleader of the Starlight Four and was able to provide a solid income through music, with bookings in clubs, radio and television. In the late 1950s, after the band was dissolved, Crichlow put his money into El Rio Café on Westbourne Park Road, which opened in the wake of the Notting Hill Race Riots. El Rio was a vibrant hub for the Caribbean community that also appealed to the growing bohemian community of West London. The space was popularised by novelist Colin MacInnes in his London Trilogy – a series of books depicting the lives of London youth and black culture in the 1950s. The venue was open almost all hours and allowed for important networks to form that dealt with issues that plagued the community, particular issues focused upon were police targeting and racism on the streets of North Kensington. At this time, far-right figures Colin Jordan and Oswald Mosley were organising for the “forced repatriation” of migrant communities, and SUS laws were leading to illegitimate convictions for the black population. Crichlow attributed the struggles experienced in the black community to white racists that supported Mosley, many of which he believed were in the police force. Throughout Crichlow’s ownership of the venue, El Rio was continually subject to police targeting. In the early 1960s, the Profumo Affair placed the venue in the centre of a scandal. This only increased police attention and Crichlow was prosecuted seven times over the venue’s operation, mainly for allowing gambling, music and dancing in an unlicensed space. In 1969, Crichlow opened the Mangrove, a thriving Caribbean restaurant that attracted famous guests such as Bob Marley, Jimi Hendrix, and Nina Simone. However, in its first year of business, it was raided twelve times, always – Crichlow said – on a Friday night, when the restaurant was busiest. The police raids disrupted customers, resulting in Crichlow losing money. The raids took place on the accusation that drugs were being sold, but they were never found. In resistance to police persecution, Crichlow organised a march to local police stations. Hundreds took part in the demonstration; however, outbreaks of violence led to police action. Nine demonstrators were charged with riot and affray in a trial known as the Mangrove 9. The trial raised discussions of institutional racism and Judge Clark’s recognition of racism within the police force led to all those charged being acquitted. The Mangrove continued to operate until 1992. Its closure followed Crichlow’s ban from the premises on what were deemed to be false accusations of drug dealing. He was later compensated £50,000 by the Metropolitan Police. Frank Crichlow and his legacy are commemorated with a plaque on the site of the Mangrove, as well as this, the Mangrove Steel band perform outside of 8 All Saints Road every year in the lead up to Panorama and the Notting Hill Carnival. Crichlow’s life and the events surrounding the Mangrove will be depicted in director Steve McQueen’s drama series for the BBC. To grasp the particularities of the 'English way of death' and the funerary traditions of modern history, we went and spoke to Julian Litten in Kings Lynn. Here are some of the images from that very revealing and fascinating day...

Our first film celebrated the legacies of pan-man, pianist and musical virtuoso Russ Henderson and the soundsystem pioneers Duke Vin and Count Suckle. Here are images of the shoots!

As part of the project, we took our cameras and our volunteer videographer Brian into Quinton Kynaston sixth form and taught the students the basics of filming on a DSLR. The students perfected their interview techniques, framed great scenes and asked open and answered open questions as part of their training.

Our young volunteers were trained by the Oral History Society's Rib Davies, here's the guys in action. A really valuable training session!Early life:

Vincent George Forbes was born in Kingston on the 25th October 1928. From birth, he was immersed in the soundsystem culture of Kingston as he grew up next door to the Success Club which held frequent dance events. Soundsystems in Jamaica: He became involved with soundsystems directly after he helped change the tyre of legendary Kingston selecter Tom Wong of Tom’s Soundsystem. Tom asked him to help him the following week and he performed exceptionally. It was through this than he obtained his nickname ‘Duke Vin’ after beating former policeman Duke Reid in a soundclash. Despite offers from a multitude of selecters in Kingston, Vin stayed loyal to Tom’s Soundsystem until he emigrated. Arrival in London: Aged 26, Vin stowed away on a ship bound for England with Count Suckle. Upon arriving in the UK he settled in Ladbroke Grove. Initially he worked for Network Rail but he then became an electrician. Vin and his friends were shocked by the dull nightlife in London at the time (‘the country is dead’) and Vin decided to build his own soundsystem. He began by playing in houses and renting out the system for £5 a night much to the chagrin of the local police. Vin soon developed a strong following in the West London area and held his first soundclash in 1958 which he won. He famously claimed to never have lost a soundclash. Soon he gained bookings at the Flamingo and Marquee Clubs and established himself as one of the leading soundmen in London. Criminal charges and later life: In the late sixties, Duke Vin was arrested and charged with pimping. During his time in prison he researched his Maroon heritage. He discovered a 1738 treaty which stated that any Maroon descendent should not have to pay any taxes to the United Kingdom. Using this information successfully sued the Inland Revenue for all the taxes he had paid over his time in England. He used this money to by a large house on the Harrow Road in which he set up an upmarket shebeen. Duke Vin was active on the soundsystem circuit throughout his life. He regularly played in London (at Notting Hill Carnival and Gaz’s Rockin’ Blues among other places) as well as internationally. He died on the 3rd November 2012 and was survived by his partner Vera, two sons and three daughters. Musical influence and legacy: The influence of soundsystems on wider musical culture is well documented but Duke Vin is seen as one of the most important figures in popularising Jamaican musical exports. He was one of the first selecters to move away from playing solely US R&B in favour of Jamaican records which foreshadowed ska. Throughout his life he maintained strong links with Jamaican producers and continued to play in Jamaica in the 1970s. Vin’s influence on mainstream white artists was also notable. He was seen as a key influence on figures such as Elton John and Georgie Fame.

Michael Speechley and Octavia Foundation staff move the shrine ready for it to go on display at the Tate Britain.

By Gopesh Pathak It seems only fitting that such an important dramatist should have led such a dramatic life. Harold Pinter’s contribution to theatrical drama spanned many decades and blossomed alongside his ventures as an actor, screenwriter and director which saw him become one of the most iconic figures of art in this country for many-a-generation. Born to Jewish parents of Eastern European origin in Hackney, Pinter renounced his Judaism after his bar mitzvah at the age of thirteen and died a vociferous anti-Israel campaigner. He was an equally vociferous campaigner for human rights – so much so that, upon receiving his Nobel Prize, the majority of his 45 minute acceptance speech was an incredibly vituperative tirade against US foreign policy. Pinter was one of the most influential voices in support of the “Stop the War” campaign in 2003. Thanks to evacuation during the war, Pinter was separated from his parents for much of his early youth. He was, however, with them in London during the Blitz; something that would go on to have a profound impact on his future political beliefs. As near in the future as 1948, in fact, which saw Pinter refuse to do his National Service. Though he is often referred to as a pacifist for his anti-war activism as well as this refusal, it is an inaccurate adjective to attribute to him as, in the tribunal relating to his refusal, Pinter claimed that he would have fought in the Second World War had he been of age to do so as that was a war against injustice. The Cold War, however, was deemed by Pinter to be a war of injustice. In the end, he was issued with a fine which his parents paid for him. Pinter began his career as an actor. Having gained a scholarship at RADA, a famous Drama school which was at the time, dominated by students of wealthy beginnings, Pinter could not stand the environment and chose to truant and read Kafka’s work in Hackney library instead. He did go on to become an actor both on stage and radio for productions of others’ plays as well as his own. But it was undoubtedly writing which gave him the most pleasure and it is his achievements as a writer that have ultimately secured his place in history books across the globe. As a writer, Harold Pinter was a masterful innovator. His manipulation of absurd theatre, colloquial dialogue in everyday settings and his use of silences have led to the term “Pinteresque” adorning the collective consciousness of the drama world (as well as the Oxford Dictionary). As for the man himself; well, he would beg to differ. He has gone on record to say that he does not have the faintest idea as to what Pinteresque could possibly be referring to, but it would be fair to say that there are certain qualities one can only find in his plays. That said, being an innovator has its own cost, as the critical reception of Pinter’s first major play The Birthday Party (1958) all too clearly revealed. Almost unanimously ridiculed (it was even branded “imbecilic” by one critic), Pinter’s deployment of what would go on to be his trademark trivial dialogue and unresolved ending was not understood by the critics who were more familiar with less ambiguity which was the accepted form at the time. Pinter’s disdain for norms in his plays was evident in his private life too and his marriage to his first wife, Vivien Merchant, without the blessing (or knowledge) of his parents (during the Jewish festival Yom Kippur!) was something which quite possibly saved his career. The poor reception of The Birthday Party saw Pinter on the verge of quitting playwriting altogether. It was Vivien who told him to continue and it was Patrick Magee, one of Pinter’s friends from his days as an actor, who managed to get a BBC radio producer to give Pinter an opportunity on the basis that if he didn’t get a job, he’d give up. From there on in, Pinter’s career went from strength to strength and he started getting appreciated for his unique approach to forming a plot. The Caretaker (1960), based on his personal experience, saw Pinter’s recognition reach new heights and moved him from being a dramatical Tahiti to a dramatical China. But, just as China is vulnerable to earthquakes, so to was Pinter and The Caretaker saw his marriage to Vivien collapse. His increased fame was at odds with Vivien Merchant’s own career as an actress, and having been the more successful partner up until that point, Vivien Merchant perhaps felt a loss of power. She also had great anger towards The Caretaker due to its plot which she felt displayed ingratitude towards people they had encountered and so, despite her becoming the epitome of women in Pinter’s plays for the rest of the ‘60s, the distance between them grew and by 1975, they had a very public split. Having had an affair with journalist Joan Bakewell, Pinter also engaged in an affair with historian and wife of a Tory MP, Lady Antonia Fraser who he later married in 1980 and stayed with until his death. It would be a great disservice to Pinter to present his plays in a summarised fashion though, it must be said, that his public perception was one of a grumpy man who was not the slightest bit interested in small talk – the mark of which is seen with the ambiguous and trivial colloquial dialogue in his plays as well as with the many accounts of his hatred of the question “How are you?” Aside from his career, Pinter was an avid cricket fan and his enthusiasm for the game saw him play for and then manage his team, the Gaieties. Pinter was diagnosed with cancer of the oesophagus in 2002. He continued his work however, directing a production of No Man’s Land and overseeing two screenplays as well as becoming increasingly active in political writing – all of this whilst undergoing treatment. In 2005, Pinter announced he would no longer write any plays. Instead of directing plays, Pinter wanted to direct his energy towards political activism. Unfortunately, this coincided with a development of septicaemia and a rare skin disease which limited his mobility. Though he continued admirably to produce material in the form of poetry and screenplay adaptations – most notably a poem entitled Cancer Cells which was widely-acclaimed for its wonderful language and dark humour – on Christmas Eve in 2008, Harold Pinter succumbed to his illness (liver cancer) and news of his death touched people all over the world. A testament to his political prowess came in the shape of a tribute from the late left-wing powerhouse Tony Benn. As for his impact on drama, that is more than words can express. Perhaps the fact he had arranged for Michael Gambon to read an extract from his play is the most glowing example of his attention to detail and desire for perfection and of how, in his most impressive shadow, even the greatest of giants seek shade. |

AuthorContent from the Waking the Dead digital media team and volunteers. Archives

April 2017

Categories |

- Home

- The Project

-

Key Figures

- Andrew Ducrow

- Anthony Perry

- Anthony Trollope

- Baron Baker

- Charles Babbage

- Count Suckle

- Duke Vin

- James Barry, Dr

- Feargus O'Connor

- Frank Critchlow

- Harold Pinter

- Howard Staunton

- Isambard Kingdom Brunel & Marc Isambard Brunel

- George Bridgetower

- Jind Kaur

- Joe Strummer

- Kate Meyrick

- Kelso Cochrane

- Michael Abbensetts

- Pearl Connor

- Russ Henderson

- Thomas Wakley

- Wilkie Collins

- William Makepeace Thackeray

- The Reformers Memorial

- The Dissenters' Chapel

- The Exhibition

- Gallery

- Waking the Dead Blog

- Contact

- Links

RSS Feed

RSS Feed