|

By Gopesh Pathak

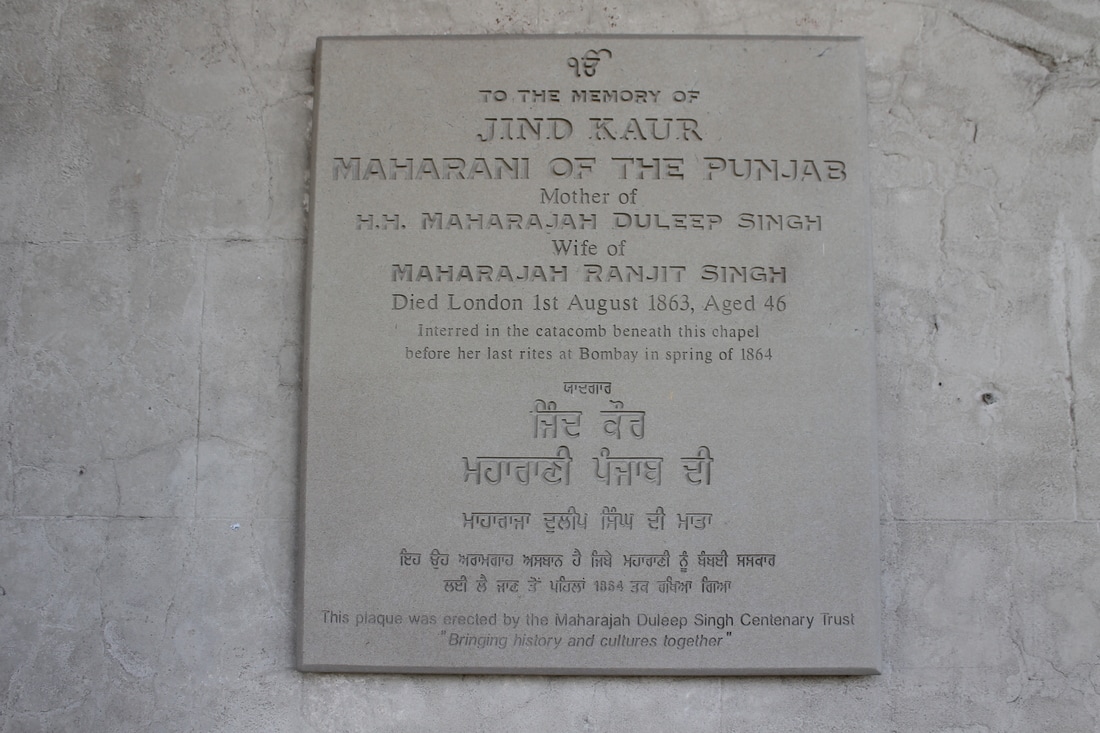

The life of Maharani Jind Kaur was a fascinating one. In fact, she may just be the most powerful woman you’ve never heard of. What’s beyond any doubt is that she was one of the most influential women of the 19th Century and that she remains an inspirational figure for those who know of her. In 1817, the earth of Gujranwala (present day Pakistan) became the earth on which a young Jind Kaur would say her first words, take her first steps and develop the mind which would terrify the British in years to come. In 1835, Jind Kaur was married to Maharajah Ranjit Singh – a marriage which would produce the events that would show just how unique Jind Kaur really was. In 1838, Jind Kaur gave birth to her only child, Duleep Singh and in 1839, her husband was to die from a stroke. Yet, tragic though it was, it seemed to be a stroke of luck for Jind Kaur, as, with her son barely a year old, Jind Kaur did not commit sati, as was the norm for widows at the time. Furthermore, all others who had hoped to take the throne from her infant son were defeated, either by Jind Kaur’s addressing of the regimental committees asking that Duleep Singh’s rights should be preserved or by deaths in mysterious circumstances. Having proclaimed herself as regent, Maharani Jind Kaur showed more defiance through difference. She gained the support of the army, took control of the government and then, to make sure there was no doubt as to who was in charge, she cast off her veil – an unprecedented move for a woman at the time. All of this was done against the backdrop of a crisis. Financially, Jind Kaur faced a next-to-empty treasury while the army that had backed her for regency expected a pay rise. Meanwhile, Duleep Singh’s kingdom was looking ever more appetising for other Maharajahs, as well as the British. In tackling these problems, Maharani Jind Kaur appointed her brother, Jawahar Singh as wazir in place of Hira Singh who had been acting as head before the Maharani’s regency, issued a fine to the relative who had taken most of the treasury, increased army pay and agreed to get Duleep Singh married to the daughter of an important member of the Sikh nobility Chatar Singh. Facing attack from Duleep Singh’s half-brother, Pashaura Singh, she surrounded him into surrender. Then, with the British looking on the riches of the Punjab with eager eyes, Jind Kaur decided to put together some resistance. When the British declared war against the Sikhs in 1845, she mobilised troops to meet the British at the Southern border of her empire to prevent the British annexation of the final piece of the Punjab jigsaw. But the British troops swept them aside and took complete control. Having initially allowed the Maharani to remain as regent and Duleep Singh to remain as Maharajah, the British, now seeing Jind Kaur’s fierce anger at their presence in her kingdom and having already seen her ability to mobilise troops for a cause, decided that something had to be done. They separated her from her son so as to halt her influence on him whilst imprisoning her in various places – each one further away from her son who by then was in England learning the English way with his friends in the Church like Queen Victoria. Still scared of her influence, the British administration deemed it necessary to launch a smear campaign against her labelling her a “Messalina” who, by taking off her veil, used her beauty to engage the lust of men and do as she pleased. But Jind Kaur was not done yet. Perhaps her most amazing feat was yet to come. Whilst in prison, she disguised herself as a servant and escaped making an 800-mile journey to Nepal where she sought refuge and was granted it. Having escaped, she then boasted to the British that she had done so by magic, as if goading them even more about their inability to control her. This cemented her place in Sikh folklore. Though Duleep Singh had requested to bring his mother to England earlier, he had not been granted permission due to the rampant fear that plagued the British rulers of India, but thirteen years after their separation, Duleep Singh used the pretence of a hunting trip in Kolkata to meet his mother and was then granted permission to bring her to England on the basis that her old age rendered her impotent against the Empire. How wrong they were. The mistake the British had made was believing their own lies. Jind Kaur’s ability was nothing to do with her looks and so her old age had no influence at all on her natural charm. In England, Jind Kaur began to reignite the flame of rebellion in her son having reintroduced him to Sikhism and rekindled the fire of patriotism. In the period after his meeting with his mother, Duleep Singh began to rebel against the British and tried to persuade the Russian Tsar to shed India of the British by invasion. With British spies following him closely, his attempt to get back his kingdom failed miserably and Duleep Singh was publicly humiliated. He spent the final years of his life pleading with Queen Victoria to forgive him. None of Duleep’s children from either of his marriages to British women had an heir and the lineage died out within a generation. But there was a flash of Jind Kaur’s genes in one of his daughters, Princess Sophia Alexandra Duleep Singh who, like Jind Kaur, showed the power of the female through her active role in the suffrage movement. As for Jind Kaur, she died in 1863 in her sleep. As cremation was illegal in Britain, Duleep Singh requested permission to take her body back to Punjab. As it was refused, her body was kept for a while in the Dissenters’ Chapel in Kensal Green Cemetery before he eventually took it to Mumbai. In 1997 a marble headstone was installed in Kensal Green Cemetery and in 2009, a memorial accompanied it. It is interesting that such an incredibly audacious and revolutionary woman is not celebrated more widely – not least in India where the Rani of Jhansi has such a high place in history. In a world in which women have only just gained – or are still gaining – political parity with men, Maharani Jind Kaur is an important symbol for women everywhere.

1 Comment

|

AuthorContent from the Waking the Dead digital media team and volunteers. Archives

April 2017

Categories |

- Home

- The Project

-

Key Figures

- Andrew Ducrow

- Anthony Perry

- Anthony Trollope

- Baron Baker

- Charles Babbage

- Count Suckle

- Duke Vin

- James Barry, Dr

- Feargus O'Connor

- Frank Critchlow

- Harold Pinter

- Howard Staunton

- Isambard Kingdom Brunel & Marc Isambard Brunel

- George Bridgetower

- Jind Kaur

- Joe Strummer

- Kate Meyrick

- Kelso Cochrane

- Michael Abbensetts

- Pearl Connor

- Russ Henderson

- Thomas Wakley

- Wilkie Collins

- William Makepeace Thackeray

- The Reformers Memorial

- The Dissenters' Chapel

- The Exhibition

- Gallery

- Waking the Dead Blog

- Contact

- Links

RSS Feed

RSS Feed